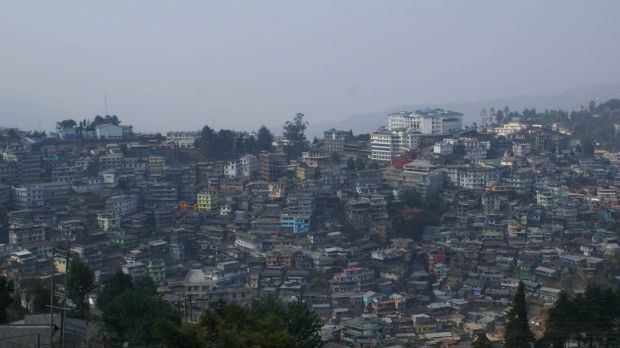

Kohima, Nagaland: Nothing ever happens in Nagaland, a predominantly Christian state tucked away amid hilly forests in India’s north-east, on the border with Myanmar. But for a fortnight, it has hogged the headlines because angry tribesmen – Nagas belong to 17 main tribes – want to halt the march of history: they want women to stay at home and not enter public life.

“Naga women work at home and in the fields. Men go to war. Men make the decisions. That’s Naga culture for centuries and we won’t allow anyone to destroy our culture,” says Vekhosayi Nyekha, co-convener of the Joint Co-ordination Committee (JCC) which represents all the tribes.

The violent protests that have paralysed Nagaland are over whether women can stand for election, hold office, and make decisions. The all-male tribal bodies are responsible for the social unrest which has seen strikes, the torching of government buildings and two deaths. They have vowed not to let the government function until women are sent back to the kitchen.

One woman in particular has got them howling for her blood. Feminist and academic Rosemary Dzuvichu is head of the English department at Nagaland University in Kohima, the capital.

“I divorced my husband after 13 years of marriage because of his violence. I raised my three children on my own. My experiences have taught me that, while I am proud of my Naga identity, society here has to change,” she says.

Dzuvichu is in her 50s and is wrapped up under layers of woollens against the cold. The house where we meet is not her home. She is in hiding.

“They threatened me and my children. They said they would burn my house down. Other women, too, have been intimidated,” she says.

In the living room, over tea and cake, she and members of the Naga Mothers’ Association, the state’s leading women’s rights group to which Dzuvichu is an adviser, are finalising a press statement in what has become a battle to define the role of women in Naga society in future.

“Men are scared of us. They think we should be happy with the scraps they throw us,” chuckles Sano Vamuzo, the 83-year-old association president.

The crux of the matter is whether Naga women can be given a leg-up to help them start participating in public life. India has a national affirmative action policy for women aimed at chipping away at centuries of powerlessness. Every locally elected body has to reserve 33 per cent of seats exclusively for women candidates. It is one of India’s rare success stories. Women have risen to participate in making decisions and play a role in public life, giving them a new confidence.

But Nagaland has never brought in this policy because of opposition by tribal bodies. Yet if any state needs affirmative action for women, it is Nagaland. The state assembly has never had a single woman legislator. Nagaland has only elected one woman to the national Parliament – in the 1970s.

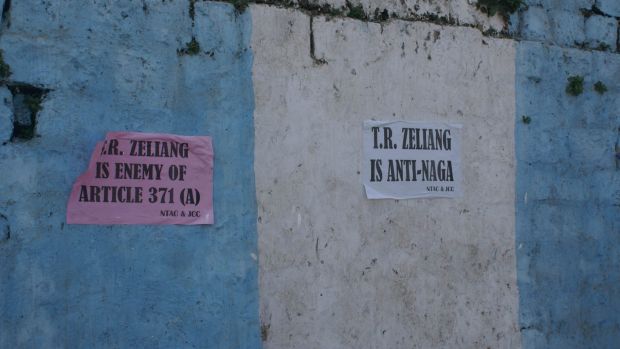

In January, Chief Minister T. R. Zeliang announced that elections to urban municipal bodies would be held on February 1, this time with 33 per cent reservation. Tribal bodies erupted in anger, warning women candidates that they would be excommunicated from their tribes. Instead of upholding the law in the face of street violence, Zeliang postponed the poll on January 30.

The war cry of the tribal bodies is “Naga culture in danger”.

“In Naga society, a woman is not equal to a man. We give women all respect but they cannot make decisions. Even in our village councils, women speak only if they are invited to give their opinion to the men. Giving women equality will destabilise our society and our ancient customs,” says Hokiye Sema, president of the Central Naga Tribal Council.

In their defence, the tribesmen cite an article of the Indian constitution which permits the Nagas, as a proud and independent ethnic group, to preserve their distinctive identity and frame their own laws accordingly.

Even the British handled the warrior Nagas with care. True, the missionaries converted them to Christianity. Baptist churches – plain buildings with huge wooden crosses – dot the skyline of this bustling town, sprawled out on the hillside.

But the British took care not to subjugate the Nagas totally, letting them live their own life, perhaps unnerved by the Naga tradition of headhunting and preserving the heads of their enemies as trophies. Even today, tribesmen wear skulls in their headgear, albeit those of animals rather than humans.

On the streets, youths from the Angami tribe stand at traffic intersections. Dressed in jeans, black leather jackets and daffodil-yellow Angami necklaces, they stop government vehicles from passing. “We won’t let the government function ’til this rule has been withdrawn,” says one youth.

Another young man, Matthew Yhoma, a stocky and rubicund 28-year-old, is a government employee in the rural affairs department and a father of two young children. He needs a lift to another part of Kohima. During the journey, he explains his opposition to equality.

“For us, affirmative action is actually an insult given the high standing and respect that Naga women already enjoy. They don’t need special policies. Nagaland is not like other parts of India. We have no custom of dowry, no female foeticide. Boys and girls are equally loved,” he says.

Warming to this theme, he goes on: “The only women demanding change are spinsters and divorced women. Other women accept our system in which decision making is done by men.

“Women can only take kitchen decisions. We take the big ones,” Yhoma adds, in all seriousness.

The fact is, as Dzuvichu points out, Nagaland’s special status has allowed unfettered discrimination in the name of “culture”. Naga women have no power: village councils are dominated by men. Naga women have no resources; Naga women cannot own land. “With no access to resources, how can women function as full citizens?” she asks.

Dzuvichu’s father was different. He educated her and her four sisters. “He gave us all property and a large paddy field, which we share. I was only able to raise my children because of my family’s support. But other women don’t have such support. Naga society has demarcated roles for men and women in which women are at the mercy of men. It was only after my divorce and everything I went through that I realised how everything is stacked against them,” she says.

The editor of the Nagaland Page, Monalisa Changkija, says Naga men fear that allowing women to participate in the urban civic bodies will destabilise the social dynamic between men and women. “Men feel this could percolate to the villages, which in turn could upset how Naga society has functioned for centuries, with men being in control,” she says.

In the congested and polluted city centre, some young women are enjoying chicken fried rice at Dream Cafe. Like most young Naga women, they are made up, fashionably dressed and immaculately groomed. Women elsewhere in India admire women from this region for their effortless chic. In Kohima, all the young women look distinctly Westernised.

Dream Cafe’s TV is showing the latest Benetton commercial. Against images of Indian women at work and play, the narrator talks of how they want “half the world, half the jobs, half the decision making”.

The women exchange wry looks. “This ad should be shown to Naga men. India is behind the rest of the world on women’s rights and Nagaland is behind the rest of India. It makes me hang my head in shame,” says Neidonu Nuh.

The JCC is pushing for Zeliang’s resignation and a rollback of the reservations policy. The streets are tense. Every day, shop owners pull down their shutters early in case of trouble. A bandh, or strike, on Monday shut down the entire state.

The JCC is pushing for Zeliang’s resignation and a rollback of the reservations policy. The streets are tense. Every day, shop owners pull down their shutters early in case of trouble. A bandh, or strike, on Monday shut down the entire state.

In the living room, Dzuvichu and her colleagues are also digging in their heels. She dismisses the JCC’s assertion that letting women be elected will destroy Naga culture. For one, she says, culture is not static, it evolves, and it cannot be against public policy.

“For another, the two are not related. Elections to urban civic bodies are a new concept that old Naga society didn’t even know about, so the customary laws can’t be applied to these new practices like elections. The two issues are totally distinct,” she says.

What should Chief Minister Zeliang do?

“Enforce the law. As well as being Nagas, we live under the Indian constitution, and if the constitution guarantees us certain rights, we want them,” Dzuvichu says.

Source: www.smh.com.au